Title:

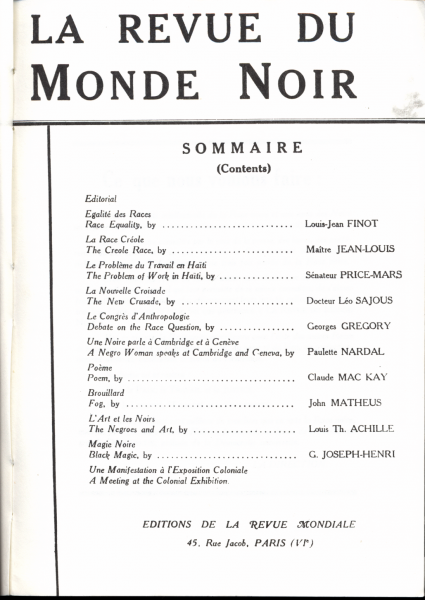

La Revue du monde noir / Review of the Black World

Date of Publication:

Nov. 1931 – Apr. 1932

Place of Publication:

Paris, France

Frequency of Publication:

Monthly, 6 issues

Circulation:

Unknown

Publisher:

Unknown

Physical Description:

9.5″ x 6.5″; plain white paper, simple block print;table of contents; manifesto (“Our Aim”) in inaugural issue; editorials; essays; reports; illustrations; poetry; photographs; illustrations; short stories; reviews; announcements (“Our Next Issue”); no advertisements. Format order varies by issue. Color remains consistent throughout run. Each issue contained approximately 60 pages. Published in French and English.

Price:

5 francs / 30 cents per issue

Editor(s):

Paulette Nardal

Leo Sajous

Associate Editor(s):

Andree Nardal

Jane Nardal

Clara Shephard

Louis-Jean Finot (Collaborators)

Libraries with Original Issues:

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library (Oak Street facility); New York Public Library; Carleton University Library; Bibliotheque Nationale de France; Yale University Library (Beinecke)

Reprint Editions:

Nendeln/Liechtenstein: Kraus Reprint, 1969; Paris: Jean-Michel Place, 1992, with a preface by Louis Thomas Achille.

La Revue du monde noir was founded in 1931 by Paulette Nardal of Martinique and Leo Sajous of Haiti as a literary manifestation of the Nardal sisters’ salon in Clamart, France. It was at the Clamart salon that the concept of a collaborative monthly, bilingual, multiracial magazine was conceived. Under cooperative editorial management, the inaugural issue of La Revue du monde noir was published in November of 1931. La Revue was the first magazine of its kind, as at the time there was “no competing bilingual, panblack literary or cultural magazine in France or imported from the United States” (Sharpley-Whiting 55). La Revue’s statement of purpose—“Our Aim”—in the first issue established its intention to encourage creative dialogue among and across the African diaspora: to “create among the Negroes of the entire world, regardless of nationality, an intellectual, and moral tie, which will permit them to better know each other to love one another, to defend more effectively their collective interests and to glorify their race” (Editorial Management 2). La Revue provided a vehicle primarily for sociological, literary, and cultural dialogue rather than political commentary; in this sense, the magazine was quite literally a review, not a journal or newspaper. The magazine was partly funded by the Ministry of Colonies, making overtly political subject matter off limits (56). La Revue published editorials, articles, poetry, short stories, book reviews, and letters to the editor on subjects related to the African diaspora in Cuba, the United States, Liberia, Ethiopia, France, and others.

Throughout the magazine’s run and despite it’s self-proclaimed apolitical nature, the French government—forever on the lookout for Communist or Garveyist sentiments among black Francophones—closely followed La Revue’s content and its editors’ activities. As Louis Achilles relates in the magazine reprint’s preface, administrators from the Ministry of Colonies withdrew monetary support, and, vexed by funding issues, the magazine ceased publication after six issues (Achilles, preface xi).

On the third page of the inaugural issue of La Revue du monde noir (November 1931), the magazine management defines the magazine’s goals in a preface entitled “Our Aim” :

“To give to the intelligentia of the black race and their partisans an official organ in which to publish their artistic, literary and scientific works.

To study and to popularize, by means of the press, books, lectures, courses, all which concerns NEGRO CIVILIZATION and the natural riches of Africa, thrice sacred to the black race.

The triple aim which LA REVUE DU MONDE NOIR will pursue, will be: to create among Negroes of the entire world, regardless of nationality, an intellectual, and moral tie, which will permit them to better know each other to love one another, to defend more effectively their collective interests and to glorify their race.

By this means, the Negro race will contribute, along with thinking minds of other races and with all those who have received the light of truth, beauty and goodness, to the material, the moral and the intellectual improvement of humanity.

The motto is and will continue to be:

For PEACE, WORK and JUSTICE

By LIBERTY, EQUALITY and FRATERNITY

Thus, the two hundred million individuals which constitute the Negro race, even though scattered among the various nations, will form over and above the latter a great Brotherhood, the forerunner of universal Democracy.” (3)

La Revue du monde noir was the product of a collaborative editorial effort born of the Nardal sisters’ salon in the Parisian suburb Clamart, France. While Paulette Nardal was the chief founder and editor, editorial collaboration included: Paulette, Jane, and Andree Nardal, Martiniquan sisters who moved to Paris to attend university and hosts of the Clamart salon; Leo Sajous, a Haitian scholar specializing in Liberian issues; Clara Shephard, an African American educator and editor of the magazine’s English translation; and Louis-Jean Finot, who was described in a French police report as “a dangerous Negrophile married to a black violinist” (Sharpley-Whiting 55).

For the purpose of this index entry, extensive biographical description will be limited to the primary founder, publisher, and editor of La Revue, Paulette Nardal.

Paulette Nardal (1896 – 1985)

Editor: 1931 – 1932

Born in Martinique in 1896, Paulette Nardal was the youngest of seven sisters. Along with her sisters Jane and Andrée, she moved to Paris for university. In Paris she obtained a “licence ès lettres anglaises”—or, English major—from the Sorbonne (Sharpley-Whiting 48). Along with her sisters she hosted an ethnically diverse and gender-inclusive salon in Clamart, the birthplace of La Revue du monde noir. She wrote for Aimé Césaire’s paper, L’Etudiant Noir, and later co-founded the newspaper La Dépêche Africaine, along with La Revue du monde noir (49). Her work in each of these publications, which varied in genre and subject matter, reflected an interest in exploring black literature and culture on a global scale. She wrote essays, journalistic pieces, and short stories on subjects ranging from Caribbean women, black art, and colonialism. Despite La Dépêche Africaine being shut down by the French government, Nardal was commissioned by the French government to write a guidebook on Martinique (49). A devout Catholic and feminist, Nardal never married.

In her role as editor of La Revue Nardal became a cultural intermediary between Harlem Renaissance writers and Francophone writers from Africa and the Caribbean, three of whom would go on to found the Négritude movement: Aimé Césaire, Léopold Senghor, and Léon Damas (Ikonne 66).

Her contributions to the Négritude movement, too, are often overlooked; while Leopold Senghor and Aimé Césaire are often touted as the founders of Negritude, Nardal contends that the men “took up the ideas tossed out by us and expressed them with more flash and brio…we were but women, real pioneers—let’s say we blazed the trail for them” (Hymans 36). Following Nardal’s death in 1985, Aimé Césaire paid honored Paulette Nardal as an initiator of the Négritude movement; he named a square in Fort-de-France, the capital of Martinique, in her honor (36).

Louis-Thomas Achille

“The Negroes and Art”

“Nos Enquetes”

Lionel Attuly

“Duet”

“On the World Crisis Considered as a Topic of Interview”

“The Patient”

Jaques Augarde

“Poem”

Jean L. Barau

“Stenio Vincent, Statesman”

P. Baye-Salzmann

“Negro Art, Its Inspiration and Contribution to Occident”

“Islamism or Christianity?”

M. Bazargan

“An Answer to “Remarks on Islamism””

L. Th. Beaudza

“Rise and Decline of a Doctrine”

“Open Letter to Admiral Castex”

H.M. Bernelot-Moens

“Can Humanity be Humanized?”

Carl Broud

“Creole Cadences”

Aaron Douglas

“Foundry”

Gisele Dubouille

“New Records of Negro Music”

Felix Eboue

“Elephants and Hippopotamuses”

“The Banda, their Musique and Language”

Raymond Ecart

“A Book of International Merit”

Joseph Folliet

“New Books: Le Droit de colinasation”

Louis-Jean Finot

“Race Equality”

Leo Frobenius

“Spiritualism in Central Africa”

Mme. Grall

“The Tom-Tom Language of the Africans”

Gilbert Gratiant

“High Sea”

E. Gregoire-Michele

“Is the mentality of Negroes inferior to that of white men?”

Georges Gregory

“Debate on the Race Question”

Roberte Horth

“A Thing of No Importance”

“Le Taciturne”

Langston Hughes

“I, Too”

Maitre Jean-Louis

“The Creole Race”

G. Joseph-Henri

“Black Magic”

Flavia Leopold

“The Vagabond”

Etienne Lero

“Poems”

“Evelyn”

“Book Reviews: Jungle Ways”

Cugo Lewis

“Molocoye Tappin (Terrapin)”

Margaret Rose Martin

“The Negro in Cuba”

John Matheus

“Fog”

Claude Mckay

“Poem”

“Spring in New Hampshire”

Rene Menil

“Magic Island”

“Othello” (“Un poeme inedit de”)

“Views of Negro Folklore”

Andree Nardal

“Notes on the Biguine Creole (Folk Dance)”

Paulette Nardal

“A Negro Woman Speaks at Cambridge and Geneva”

“Awakening of Race Consciousness”

Colonel Nemours

“History of the Family Descendants of Toussaint-Louverture”

C. Renaud-Molinet

“Remarks on Islamism”

G.D. Perier“Racial Poetry”

Senateur Price-Mars

“The Problem of Work in Haiti”

Magd. Raney

“Night Vigil”

Rolland Rene-Boisneuf

“Colonial Economics: The Banana Question”

Leo Sajous

“The New Crusade”

“American Negroes and Liberia”

“Liberia and the World Politics”

Pierre B. Salzman

“An Opinion on Negro Art”

Clara W. Shephard

“Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute”

“The Utility of Foreign Languages for American Negroes”

Emile Sicard

“A Meeting at the Colonial Exhibition”

“Mutual Ignorance”

Philipe Thoby-Marcelin

“Poem”

“Poem of Another Season”

“Stanza”

“Destiny”

Walter White

“The Fire in the Flint”

Ydahe (pseudonym for Jane Nardal)

“Night Falls on Karukera Island”

Doctors A. Marie and Zaborowski

“Cannibalism and Lack of Vitamins”

Guetatcheou Zaougha

“The Renaissance of Ethiopia”

Philipe de Zara

“The Awakening of the Black World”

Guy Zuccarelli

“Docteur Price-Mars, a portrait”

“A Lecture on the Voodoo Religion”

“A Stage in Haiti’s Evolution”

Edwards, Brent Hayes. The Practice of Diaspora: Literature, Translation, and the Rise of Black Internationalism. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2003.

Hymans, J.L. Léopold Sédar Senghor: An Intellectual Biography. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 1971.

Ikonne, Chidi. Links and Bridges: A Comparative Study of the Writings of the New Negro and Negritude Movements. Nigeria: University Press, Nigeria, 2005.

Jack, Belinda E. Negritude and Literary Criticism : The History and Theory of ” Negro-African ” Literature in French. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996

“La Revue du monde noir.” Liberation Journals Index. Brown University

Sharpley-Whiting, Tracy D. Negritude Women. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2002.

Sourieau, Marie-Agnes. “La Revue du Monde Noir.”Encyclopedia of Latin American Literature. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1997. Print.

“La Revue du monde noir” compiled by Taylor Hamrick (Class of ‘13, Davidson College)