Title:

Transition

Subtitles varied:

an international quarterly for creative experiment (Summer 1928 – June 1930)

an international workshop for orphic creation (Mar. 1932 – Feb. 1933)

an intercontinental workshop for vertigralist transmutation (July 1935)

a quarterly review (June 1936 – 1937)

Date of Publication:

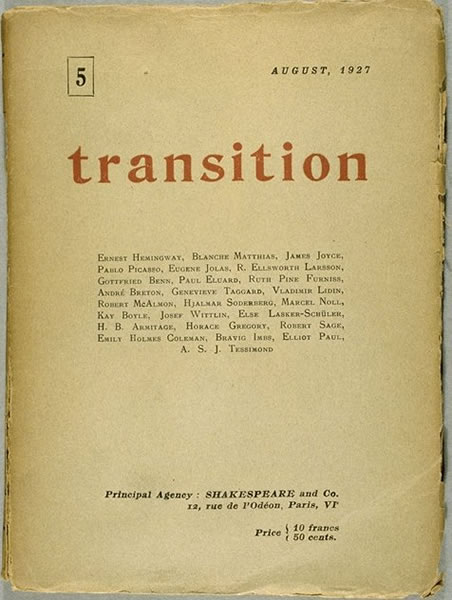

Apr. 1927 (no. 1) – Spring 1938 (no. 27)

Publication suspended between the Summer of 1930 and the Spring of 1932

Place(s) of Publication:

Paris, France (Apr. 1927 – Mar. 1928)

Colombey-les-deux-Eglises, France (Apr. 1928 – Spring 1938)

Frequency of Publication:

Monthly (April 1927 – March 1928)

Quarterly (Summer 1928 – June 1930)

Irregular (1930 – Spring 1938)

Circulation:

1000+ in 1927

Publisher:

Shakespeare and Co., 12 Rue de l’Odeon, Paris

Bretano, 1 West 47th St, New York

Physical Description:

The magazine was 5.5″ x 9″. Often ran over 200 pages. Has supplement entitled “Transition pamphlet.”

Price:

$5 per subscription

Editor(s):

Eugene Jolas

Associate Editor(s):

Elliot Paul (Apr. 1927 – Mar. 1928)

Robert Sage (Oct. 1927 – Fall 1928)

James Johnson Sweeney (June 1936 – May 1938)

Libraries with Original Issues:

Northwestern University; University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; Princeton University; Columbia University; Brown University: University of Wisconsin, Madison; University of Iowa

Reprint Editions:

New York: Kraus Reprint Co., 1967

Some scanned issues on Gallica.fr

Eugene Jolas began his little magazine career with The Double Dealer, but he found the magazine overly restrictive, and hoped to create a transatlantic place of refuge for experimental writers to express themselves without fear of criticism. With the help of his wife, translator and printer Maria Mcdonald, Jolas created his own creative magazine, transition. The magazine aimed to combat the rigidity of American political and artistic views. Jolas’s travels to Paris helped him fuse the spirit of French modernism with the rebellion and innovation of American writers. The first issue, a heavy, 150-page magazine, was published in 1927 after a long struggle with foreign printing complications.

The magazine quickly became a “laboratory of the word” – a place to experiment with and shape new ideas – for Modernists such as James Joyce, William Carlos Williams, H. D., Alfred Kreymborg, Gertrude Stein, and Muriel Rukeyser (Hoffman 176). Political writers, Harlem Renaissance voices, works with psychoanalytic qualities, multinational and multilingual works, and other various artistic schools harmonized in the varied pages.

transition eventually morphed from a synthesis of Expressionism and Surrealism into a more philosophical combination of irrational surrealism and language innovation, which the Jolases labeled Vertigralism. transition expanded and slightly shifted its focus, and embraced new media such as sculpture, civil rights activism, carvings, criticism, and cartoons. The diversity of both form and content brought the magazine success for more than ten years. During transition‘s run, Jolas created new literary philosophies, provided inspiration to the avant-garde tradition, and published works that became canonical classics.

The editors issued the following statement of purpose in the magazine’s third year:

PROCLAMATION

“Tired of the spectacle of short stories, novels, poems and plays still under the hegemony of the banal word, monotonous syntax, static psychology, descriptive naturalism, and desirous crystallizing a viewpoint….

We hereby declare that:

1. The revolution in the English Language is an accomplished fact.

2. The imagination in search of a fabulous world is autonomous and unconfined

(Prudence is a rich, ugly old maid courted by Incapacity…. Blake)

3. Pure poetry is a lyrical absolute that seeks an a priori reality within ourselves alone.

(Bring out number, weight and measure in a year of dearth…. Blake)

4. Narrative is not mere anecdote, but the projection of a metamorphosis of reality.

(Enough! Or Too Much! … Blake)

5. The expression of these concepts can be achieved only through the rhythmic “Hallucination of the Word”. (Rimbaud).

6. The literary creator has the right to disintegrate the primal matter of words imposed on him by text-books and dictionaries.

(The road of excess leads to the palace of Wisdom… Blake)

7. He has the right to use words of his own fashioning and to disregard existing grammatical and syntactical laws.

(The tigers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction … Blake)

8. The “litany of words” is admitted as an independent unit.

9. We are not concerned with the propagation of sociological ideas, except to emancipate the creative elements from the present ideology.

10. Time is a tyranny to be abolished.

11. The writer expresses. He does not communicate.

12. The plain reader be damned.

(Damn braces! Bless relaxes! … Blake)

–Signed: Kay Boyle, Whit Burnett, Hart Crane, Caress Crosby, Harry Crosby, Martha Foley, Stuart Gilbert, A. L. Gillespie, Leigh Hoffman, Eugene Jolas, Elliot Paul, Douglas Rigby, Theo Rutra, Robert Sage, Harold J. Salemson, Laurence Vail.”

“Proclamation.” No. 16-17 (June 1929): 13.

Eugene Jolas (Oct. 26, 1894 – May 26, 1952)

Editor: Apr. 1927 – Spring 1938

New Jersey born John George Eugène Jolas’s cultural standpoint was influenced by his German mother and his French father. He moved to Alsace-Lorraine, France at a young age, where he faced the tensions between French and German languages, societies, and politics. These conflicts, and apprehensions about the German army draft, inspired Jolas to return to America in 1909 with a more poly-national worldview. Though faced with typical immigrant struggles such as poor employment opportunities, language acquisition, and ethnic divisions, Jolas eventually emerged successful as both a journalist and a poet in the American literary scene. He then moved to Paris where he met his wife, Maria McDonald, and began formulating ideas for a little magazine, transition. The magazine marked, as biographers Kramer and Rumold point out, Jolas’ “greatest literary project and most enduring achievement ” (Babel xv).

Samuel Beckett

“Assumption”

“For Future Reference”

Kay Boyle

“Dedicated to Guy Urquhart”

“Polar Bears and Others”

“Theme”

Hart Crane

“O Carib Isle!”

H. D.

“Gift”

“Psyche”

“Dream”

“No”

“Socratic”

Max Ernst

Jennes Filles en des Belles Poses

The Virgin Corrects the Child Jesus Before Three Witnesses

Stuart Gilbert

“The Aeolus Episode in Ulysses”

“Function of Words”

“Joyce Thesaurus Minusculus”

Juan Gris

Still Life

Ernest Hemingway

“The Sentence”

“Three Stories”

“Hills Like White Elephants”

James Joyce

“Work in Progress” (Finnegan’s Wake)

Franz Kafka

“Metamorphosis”

Alfred Kreymborg

From Manhattan Anthology

Pablo Picasso

Petite Fille Lisant

Muriel Rukeyser

“Lover as Fox”

Gertrude Stein

“An Elucidation”

“As a Wife Has a Cow A Love Story”

“The Life and Death of Juan Gris”

“Tender Buttons”

“Made a Mile Away”

William Carlos Williams

“The Dead Baby”

“The Somnambulists”

“A Note on the Recent Work of James Joyce”

“Winter”

“Improvisations”

“A Voyage to Paraguay”

Hoffman, Frederick J., Charles Allen, and Carolyn F. Ulrich. The Little Magazine: A History and a Bibliography. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1947.

“Ernest Hemingway In His Time: Appearing in the Little Magazine.” Transition. 18 Nov. 2003. Special Collections Department. University of Delaware Library. 22 July 2009.

Jolas, Eugene and Robert Sage, eds. Transition Stories: Twenty-three Stories from “Transition.” New York: W. V. McKee, 1929.

Kramer, Andreas and Rainer Rumold, eds. Jolas, Eugene. Man from Babel. New Haven: Yale UP, 1998.

Nelson, Cary. Repression and Recovery: Modern American Poetry and the Politics of Cultural Memory, 1910-1945. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989.

transition. 1927 – 1938. New York: Kraus Reprint Corp., 1967.

“Transition” compiled by Alice Neumann (Class of ’06, Davidson College)