Title:

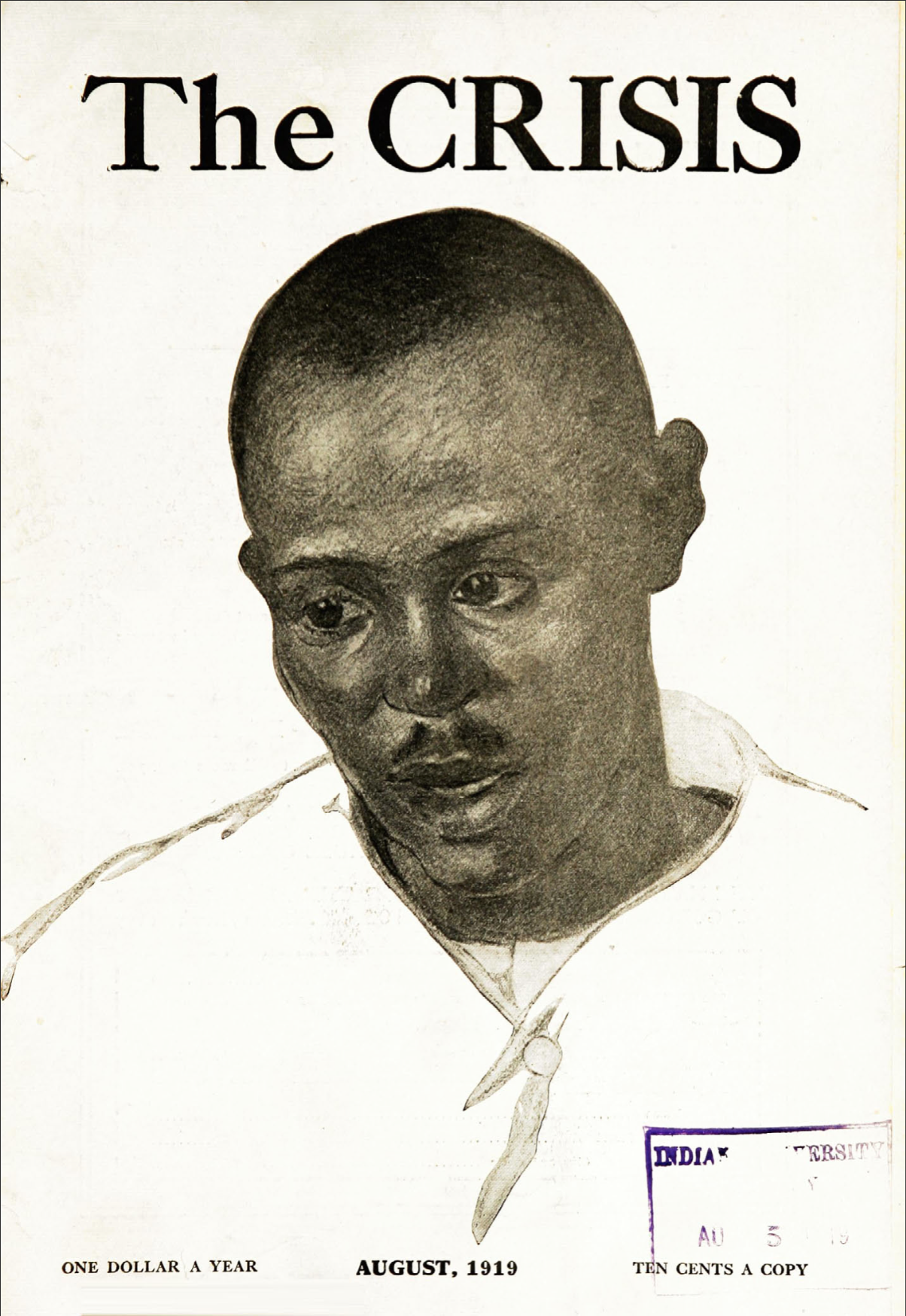

Crisis: A Record of the Darker Races

Date of Publication:

Nov. 1910 (1.1) – Feb./Mar. 1996 (103:2)

Continued by the New Crisis, July 1997 (104:1) – Mar./Apr. 2003 (110:2)

Continued as The Crisis, May/June 2003 (110:3) – Present

Place(s) of Publication:

New York, NY, (Nov. 1910 – Feb./Mar. 1996)

Baltimore, MD (July 1997 – Mar./Apr. 2003)

Frequency of Publication:

Bimonthly

Circulation:

Average monthly circulation: 10,500 (1934)

Publisher:

NAACP: 1910 -1933

Crisis Publishing Company, Inc. (subsidiary of NAACP), New York: 1933 – 1996

Crisis Publishing Co., Inc., Baltimore, Maryland: 1997 – 2003

Physical Description:

15-35 pages of editorials, reviews of literature and theater, poetry, illustrations, photographs. Advertisements at front and back, many for universities. Frequently appearing sections include “The N. A. A. C. P.” “What to Read,” “Opinion,” “Along the Color Line.”

Price:

Unknown

Editor(s):

W. E. B. Du Bois (Nov. 1910 – July 1934)

Associate Editor(s):

None

Libraries with Original Issues:

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; Northwestern University; Tuskegee University; University of California, Los Angeles; Library of Congress; University of Delaware; University of Georgia; Harvard University; University of Texas, Austin; University of Virginia

Reprint Editions:

New York: Negro Universities Press, 1969

New York: Arno, 1969

Ann Arbor, Michigan: University Microfilms International [microform]

Though The Crisis: A Record of the Darker Races started as the official publication for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), it became a forum for expressing opinions on racial problem. Today it catalogues the extensive progress of African Americans while remaining a political vehicle for the civil rights of minorities.

The magazine addressed all aspects of the African American community, commentating on everything from churches, businesses, and schools, to literature and music. A notable feature of the magazine was Editor W.E.B. Du Bois’ editorial page, which stood “for the right of men, irrespective of color or race, for the highest ideals of American democracy, and for reasonable but earnest and persistent attempt to gain these rights and realize these ideals” (Du Bois).

The Crisis has undergone many challenges, from being cautioned by the United States Department of Justice for statements harmful to the war effort to being held up by the Post Office because of articles that “supposedly inspired Negro acts of violence.” Yet for more than 90 years, The Crisis has remained a journal of literary achievements, and serves as a record of the social and political history surrounding African Americans’ fight for civil rights.

W. E. B. Du Bois’ voice was ever-present when he served as editor of Crisis. Fittingly, he offered the opening issue’s editorial describing the mission of his magazine:

“The object of this publication is to set forth those facts and arguments which show the danger of race prejudice, particularly as manifested today toward colored people. It takes its name from the fact that the editors believe that this is a critical time in the history of the advancement of men. Catholicity and tolerance, reason and forbearance can today make the world-old dream of human brotherhood approach realization; while bigotry and prejudice, emphasized race consciousness and force can repeat the awful history of the contact of nations and groups in the past. We strive for this higher and broader vision of Peace and Good Will.

“The policy of THE CRISIS will be simple and well defined:

“It will first and foremost be a newspaper: it will record important happenings and movements in the world which bear on the great problem of inter-racial relations, and especially those which affect the Negro-American.

“Secondly, it will be a review of opinion and literature, recording briefly books, articles, and important expressions of opinion in the white and colored press on the race problem.

“Thirdly, it will publish a few short articles.

“Finally, its editorial page will stand for the rights of men, irrespective of color or race, for the highest ideals of American democracy, and for reasonable but earnest and persistent attempts to gain these rights and realize these ideals. The magazine will be the organ of no clique or party and will avoid personal rancor of all sorts. In the absence of proof to the contrary it will assume honesty of purpose on the part of all men, North and South, white and black.”

“Editorial.” 1:1 (Nov. 1910): 10.

W. E. B. Du Bois (Feb. 23, 1868 – Aug. 27 1963)

Editor: Nov. 1910 – July 1934

In his own words, William Edward Bughardt Du Bois was born “by a golden river and in the shadow of two great hills” in Great Barrington, Massachusetts in 1968, the year when “the freedmen of the South were enfranchised and […] took part in government” (Du Bois 8). He graduated from Fisk College in Nashville, Tennessee in 1888 and became the first African-American to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard in 1895. While teaching at Wilberforce College and Atlanta University, Du Bois published The Souls of Black Folk, a collection of essays expressing the conflicting anger and sadness of blacks in a supposedly modern America. Du Bois founded and edited two little magazines, The Moon and The Horizon, before becoming the founding editor of The Crisis, an NAACP-sponsored publication which he edited for twenty-five years. A prolific and persuasive writer, Du Bois was a caustic, active, and well-published figure during the nascent civil rights struggles in 20th century America.

Gwendolyn Bennett

“To Usward”

“Pipes of Pan.”

Otto Bohanan

“The Washer Woman”

Lyndel Bower

“The First Stone”

Charles Chesnutt

“The Doll”

Countee Cullen

“Mary Mother of Christ”

Langston Hughes

“The Negro Speaks of Rivers”

“Song for a Suicide”

Virginia Jackson

“Africa”

Roscoe Jamison

“Negro Soldiers”

Georgia Douglas Johnson

“A Sonnet: TO THE MANTLED!”

“Let Me Not Lose My Dream”

“Motherhood”

“Shall I Say, ‘My Son, You’re Branded?’”

Alfred Kreymborg

“Red Chant”

Vachel Lindsay

“The Golden-Faced People”

Claude McKay

“If We Must Die”

“The Void”

“Skeleton”

Jean Toomer

“Song of the Son”

Lew Wallace

“The Beginning of Sorrow”

Lucian Watkins

“Ebon Maid and Girl of Mine”

“About the Crisis.” The Crisis Online. NAACP. 13 July 2009.

“Du Bois: The Activist Life.” Special Collections and University Archives. 2004. W. E. B. Du Bois Library: University of Massachusetts, Amherst. 13 July 2009.

The Crisis. New York: Crisis Pub. Co, 1910 – 1966.

Marable, Manning. W. E. B. Du Bois: Black Radical Democrat. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1986.

Moon, Henry Lee. “History of the Crisis.” The Crisis: Nov. 1970. Reprinted in The Crisis Online. NAACP. 23 July 2009.

Moore, Jack. W. E. B. Du Bois. Boston: Twayne Publishing, 1981.

Rampersad, Arnold. The Art and Imagination of W. E. B. Du Bois. Massachusetts: Harvard UP, 1976.

Rudwick, Elliot. W. E. B. Du Bois: Propagandist of the Negro Protest. New York: Atheneum, 1986.

“The Crisis” compiled by Alex Entrekin & Catherine Walker (Class of ’06, Davidson College)