Issued in 1926 by Wallace Thurmond and a group of self-described “younger Negro artists,” Fire!! promoted itself as a “youthful rebellion” against the constraints of traditional aesthetics and uplift ideology—pressures exerted on African American writers to conform to white, bourgeois standards and prove the worthiness of their race (Churchill et al 65). Matthew Hannah, in “Desires Made Manifest: The Queer Modernism of Wallace Thurman’s Fire!!,” describes Fire!! as a “queer sexualities operative in Harlem through a modernist politics of aesthetic representation in direct opposition to racial uplift and sociological analysis” (Hannah 163). The magazine focused on testing the artistic limits of African American art, while highlighting the development of artists and black cultural expression over commercial success. Fire!! was only published once, supposedly because the editorial staff lacked the funds to keep the magazine going. Yet in a single issue, race, age, and sexuality created a unique intersection between the founders, contributors, and readers of Fire!!.

One factor that may have contributed to Fire!!‘s short lifespan was tensions about the racial make up of its audience. While the creators wanted to represent and appeal to black artists and audiences, they were dependent on white patrons and readers. Wallace Thurman, founding editor, argued that there was a “fundamental difference between “the Negro… and their Nordic neighbor” (Fabre & Feith 78). Aaron Douglas examined how the Harlem Renaissance attracted a following made up of predominantly white patrons, and was tasked with reaching out to a black audience in hopes of gathering support for “their own artists” (Fabre & Feith 78). Despite the magazine’s reliance on white readers, Fire!!’s contributors criticized and expressed outrage at white patrons’ inability to “understand authentic black cultural expression” (Fabre & Feith 78).

We are all under thirty. We have no get-rich-quick complexes. We espouse no new theories of racial advancement, socially, economically, or politically. We have no axes to grind. We are group-conscious. We are primarily and intensely devoted to art” (Fabre & Feith 78).

Douglas and the other contributing artists and writers expressed no desire to conform to white stereotypes of African Americans, and they articulated their sole commitment to producing art.

Fire!! garnered mixed reviews in the black press, ranging from affirmative to outright condemnation (Churchill et al 66). Would white readers of Fire!! have felt offended by the staff’s comments about its white readership, and turned away from the magazine entirely? Would Fire!! have seen a significant drop in readership after driving these white readers away? Without knowing the racial make up of its readership, we may never know the answers to these questions, particularly because it appears that Thurman and the other founders of Fire!! couldn’t come up with the money for the second issue of the magazine. Thurman himself was described to have had a “modest salary” before the beginning of Fire!!, and was “constantly broke,” spending much of his money on alcohol and partying (Potter 29). Ultimately, it cannot be determined if Fire!!’s lifespan would have been affected by its publication of certain content. We can, however, question if and how a focus on racial oppression would have affected the magazine if it had published more issues as was planned. Would Thurman and Douglas’ indifference towards money-making have affected the magazines longevity? Would their attention to difference in race, age, and sexuality have turned readers away or pulled them in?

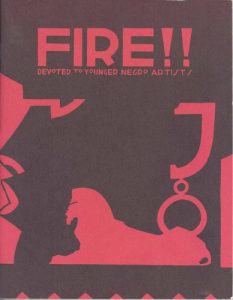

Click on the cover to browse sample pages of Fire!!