The Colored American Magazine strove to dispel traditional views of African American artists and writers and provide a space for their successes in business and literature to be published side-by-side. Originally, The Colored American had two editors: Walter Wallace and Pauline Hopkins. Hopkins was known for her vocal criticism of Jim Crow racism and her boldness in revealing the truths about being black in America during the twentieth century. Our project recognizes race issues as factors influencing the lifespans of little magazines; thus Pauline Hopkins and The Colored American are critical to our study.

According to Eurie Dahn and Brian Sweeney, The Colored American Magazine sought to reach an African American audience, but found about a third of its readers to be white (Dahn & Sweeney). Fred Randolph Moore purchased the magazine in 1904 with help from Booker T. Washington, moved it from Boston to New York, and pushed Hopkins out of her editorial position. Subsequently, its issues shifted away from political radicalism to focus on literary achievement. In turn, The Colored American’s attention to racial equality diminished. Dahn and Sweeney’s website cites white readers such as John C. Freund, co-publisher of The Music Trades Magazine (first published in 1891), as having been the force that compelled Moore to alter the original goals of the magazine. Freund was a contributor and patron of The Colored American, and repeatedly urged Hopkins to abandon her revolutionary ways of thinking and lean more towards less assertive content. Abby Arthur Johnson and Ronald Maberry Johnson write that even Washington referred to her contributions as “embarrassingly outspoken” (Johnson & Johnson 8). The change that Moore, Washington, and some candid readers were looking for was not in Hopkins’ resistant nature, and she was eventually dismissed “with brevity and faint praise” (Johnson & Johnson 9). Management also claimed that Hopkins “found it necessary to sever her relations” with the magazine on account of “ill-health”(Johnson & Johnson 8). Meanwhile, she was writing for The Voice of the Negro just one month after The Colored American‘s news of her dismissal (Johnson & Johnson 9). According to Johnson and Johnson, Hopkins “made no attempt to modify the magazine’s expressions out of consideration for the white persons from whom most of the support was obtained,” and this proved problematic in shifting the magazine towards favoring a “conciliatory attitude” (Johnson & Johnson 9).

While the changes to The Colored American magazine following Hopkins’ supposed expulsion resulted in the subsequent exclusion of progressive stories about African American individuals, it cannot be said for sure that her dismissal was based upon her radical racial expression. Moore and Washington shaped what looked like a completely new magazine, one that “stayed away from ruffling the feathers of white supporters and de-emphasized literature’s role in race politics” (Dahn & Sweeney). Despite being deemed a “race journal” in its earlier years, The Colored American’s commitment to publishing content about the black American experience eventually proved to be too subversive for its readers (Knight).

Was it the radical conversation about being black in America that Hopkins incited in each early issue that led the magazine to cease production only nine years after its first publication? Was it the magazine’s move away from this type of conversation that brought it to its end? To answer these questions would require a deeper study of the magazine’s readership in relationship to its content. Brooks Hefner and Edward Timke’s “Circulating American Magazines” project provides the foundations for such analysis, though it is not yet clear whether their study will provide data on The Colored American Magazine.

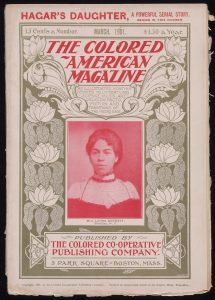

Click on the cover to browse sample pages of The Colored American.