Title:

The Fugitive

Date of Publication:

Apr. 1922 – Dec. 1925

Place(s) of Publication:

Nashville, Tennessee

Frequency of Publication:

Quarterly: (Mar. 1925 – Dec. 1925)

Bimonthly (irregular) (Feb. – Mar, 1923 – Dec. 1924)

Quarterly (Apr. 1922 – Dec. 1922)

Circulation:

Self-described as “very limited” (1.1 [April 1922]: 2)

Publisher:

The Fugitives, Nashville

Jacques Black (Business Direction, October 1923-December 1924)

Physical Description:

4 volume; 23 cm

Price:

$1 per year (Mar. 1925 – Dec. 1925)

$1.50 (June 1923 – Dec. 1924)

$1.00 (Apr. 1922 – June 1923)

Editor(s):

Robert Penn Warren (Mar. 1925 – Dec. 1925)

John Crowe Ransom (Mar. 1925 – Dec. 1925)

Donald Davidson (Aug. 1923 – Dec. 1924)

Associate Editor(s):

Jesse Wills (June 1924 – Dec. 1924)

Allen Tate (Aug. 1923 – Apr. 1924)

Libraries with Original Issues:

Vanderbilt University Library, Stanford University Library

Reprint Editions:

Fugitives (Group). The Fugitive: A Journal of Poetry. 1922-1925. New York: Johnson Reprint Corp., 1966. Print.

The publication of The Fugitive in April 1922 came as an organic step for a preexisting collective of poetry enthusiasts in Nashville, Tennessee, many of whom were affiliated with Vanderbilt University (though the magazine itself and the college remained completely separate). Sidney Hirsch, host since 1915 of bimonthly meetings to critique the members’ poetry and engage in philosophical debates, suggested that they publish their work, thus publicizing the efforts of a group who became known as the “inaugurators of the Southern literary renaissance,” as well as the “founders of New Criticism” (Cowan xv; Brooker and Thacker 504).

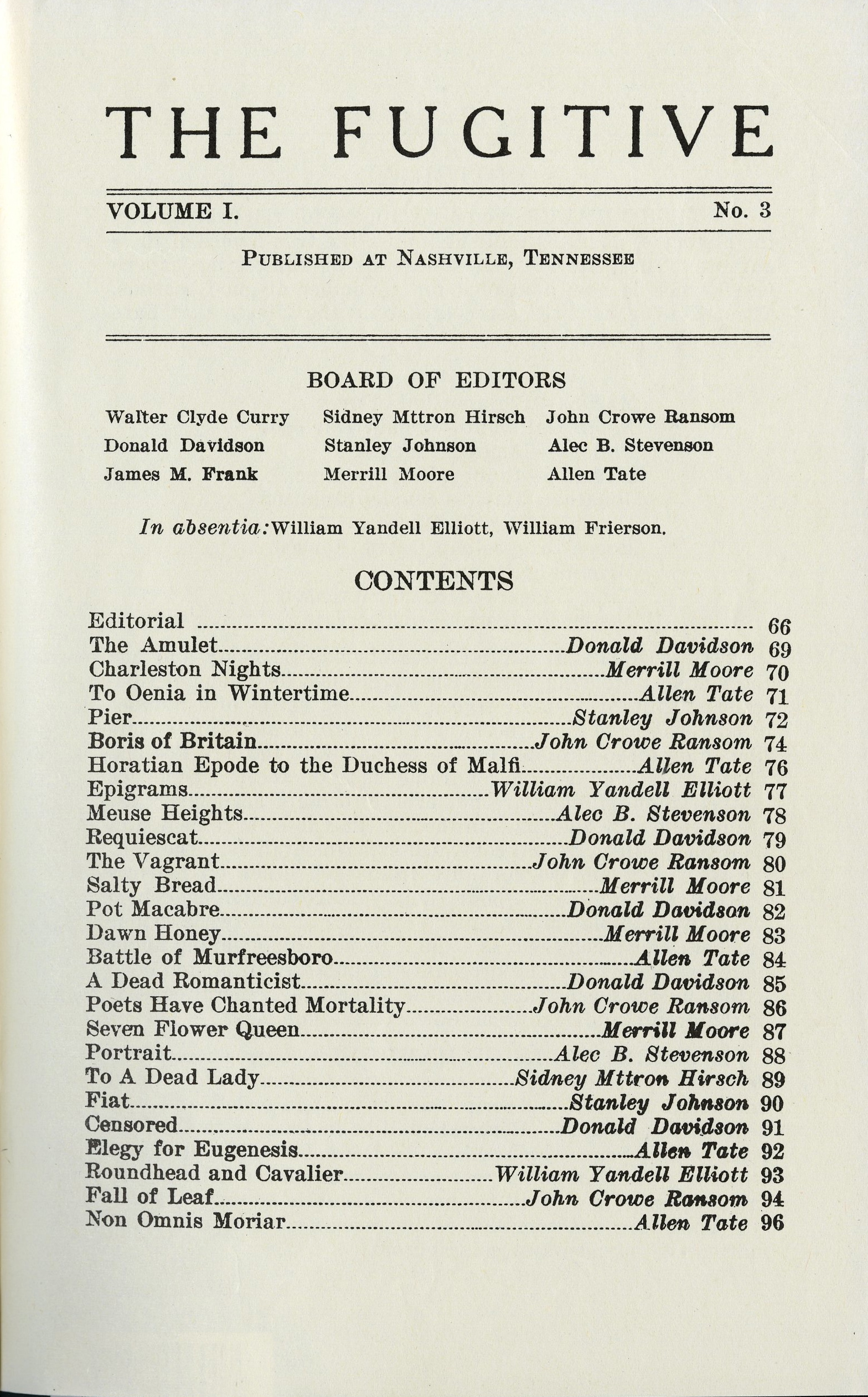

Poetry dominated the pages of The Fugitive but the publication also featured editorial pieces about poetry, details about the affiliated members’ upcoming titles, book reviews, and contest announcements. The magazine did not specify the board of editors until its third issue, and contributors published under pen-names before this point as well. Though the style and content varied among the published pieces, a the publication’s common theme was communicated in the “Forward” to the first issue: “THE FUGITIVE flees from nothing faster than the high-caste Brahmins of the Old South” (1.1 [April 1922]: 2). These “Brahmins” are not specifically defined, but the Forward shows the member’s dislike of “sentimentality” and “regional stereotyping” (Cowan 44; Kreyling 512).

The Fugitive was not what one might consider a distinctively or intentionally Southern magazine; Hoffman, Allen and Ulrich assert that “these poets showed no concern with promoting a scheme for reconstructing Southern life, except insofar as they wished to inject a fresh note into its verse” (121), and according to John Egerton, “What [the Fugitives] cared about was the craft of poetry and the intellectual stimulation they derived from writing it” (61). The board of editors stayed fairly consistent throughout the course of this publication, with a few additions along the way. It remained a predominantly male, white group. Laura Riding Gottschalk (later Laura Riding Jackson) became a member in March 1925 and was the first and only female Fugitive. Scholars frequently draw attention to the collaboration among the board of editors; indeed, even when the magazine began electing editors and associate editors in Volume II, Issue 8, the essence of the group hinged upon “the ancient policy of group-action” [2.8 (August-September 1923) 98].

The Fugitive began on an amicable note, and its discontinuation followed suit. Rather than the result of fiscal woes, the magazine’s end came about from logistical constraints and lack of a viable editor, as dramatically stated in the final issue: “The fugitives are busy people, for the most part enslaved to Mammon, their time used up by vulgar bread-and-butter occupations. Not one of them is in a position to offer himself on the alter of sacrifice” [4.4 (December 1925): 125]. Several of the writers, however, continued their salon and correspondences well past the publication of the magazine: in particular, Tate, Davidson, Ransom, and Warren became known as some of the most influential literary figures of their time.

Though not specifically deemed a manifesto, John Crowe Ransom offers the following statement of purpose in the editorial section of Volume I, Issue 2:

“THE FUGITIVE EXISTS for obvious purposes and has the simplest working system that we know of among periodicals. It puts in a single record the latest verses of a number of men who have for several years been in the habit of assembling to swap poetical wares and to elaborate the Ars Poetica. These poets acknowledge no trammels upon the independence of their thought, they are not overpoweringly academic, they are in tune with the times in the fact that to a large degree in their poems they are self-convicted experimentalists. They differ so widely and so cordially from each other on matters poetical that they all were about equally startled and chagrined when two notable critics, on the evidence of the two previous numbers, construed then as a single person camouflaging under many pseudonyms. The procedure of publication is simply to gather up the poems hat rank the highest, by general consent of the group, and take them down to the publisher.”

Ransom, John Crowe. “Editorial.” The Fugitive 1.3 (1922): 66. Rpt. in The Fugitive: A Journal of Poetry. New York: Johnson Reprint Corp., 1966. Print.

John Crowe Ransom (Apr. 30, 1888 – Jul. 3, 1974)

Co-Editor with Warren: Mar. 1925 – Dec. 1925

John Crowe Ransom was born on April 30, 1888 in Pulaski, Tennessee. He was one of the more established members of the Fugitives group at its inception, having had the prestige of being a Rhodes scholar at Oxford after graduating from Vanderbilt. Ransom was a literature professor at Vanderbilt until 1937, after which point he relocated to Kenyon College where he would create and edit The Kenyon Review from 1939 to 1959. He shifted his primary focus away from poetry, and in 1941 he published perhaps the most famous critical work of his career, The New Criticism, which called for a close, analytical approach to texts. Ransom’s fellow Fugitives influenced his volume, and New Criticism became the preeminent model for literary criticism and analysis for much of the twentieth century.

Robert Penn Warren (Apr. 24, 1905 – Sept. 15, 1989)

Co-Editor with Ransom: Mar. 1925 – Dec. 1925

Robert Penn Warren was born on April 24, 1905 in Guthrie, Kentucky. Warren impressed Ransom and Davidson with his work in their classrooms at Vanderbilt, and Tate encouraged him to get involved with the Fugitives. His first published poem appeared in the June/July 1923 edition of The Fugitive, and he joined the board of editors in February 1924. Warren would go on to have a prestigious career for his poetic and critical publications. Among the accolades for his creative work, he received the Pulitzer Prize three times, once for a novel and twice for poetry, and he was also named the national Poet Laureate in 1986. He and Cleanth Brooks edited The Southern Review from 1935 to 1942 and published three critical works that would help shape New Criticism: An Approach to Literature (1936), Understanding Poetry (1938), and Understanding Literature (1943).

Donald Davidson (Aug. 18, 1893 – Apr. 25, 1968)

Editor: (Aug. 1923-Dec. 1924)

Donald Davidson was born in Campbellsville, Tennessee on August 18, 1893. Davidson had strong ties to Vanderbilt: he received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the University, with brief interruptions due to financial struggles and World War I. He eventually became an English professor at his alma mater. Davidson was at the heart of the Fugitive group, and he had a key role in bringing each editor into a literary circle. In 1915 he met Sidney Hirsch, who would later host the official Fugitive gatherings; introduced Ransom to the Hirsch family and their literary friends; asked Tate to join the Fugitives; and Tate would later invite Warren. Davidson served as the first official editor of The Fugitive when the group created this position in September 1923, and his work on the magazine resulted in an increasing interest in “defining Southern identity” throughout his career (McDonald 247). He published several volumes of poetry, with his piece “Fire on Belmont Street” earning the South Carolina Poetry Society’s Southern Prize in 1926; reviewed southern literature from 1924 to 1930 in his column “The Spy Glass” in the Tennessean; and wrote a two part historical work called The Tennessee (1946 and 1948).

Allen Tate (Nov. 19, 1899 – Feb. 9, 1979)

Associate Editor: Aug. 1923 – Apr. 1924

Allen Tate was born on November 19, 1899 in Winchester, Kentucky. Davidson introduced Tate to the Fugitives in 1921, and Tate became the associate editor of the magazine in 1923. Tate was the “modernist zealot” of the Fugitives, with a strong interest in T.S. Eliot, and his intrigue and adamant opinions on the state of modern poetry fueled his studies and publications (Kreyling 511). In 1924 he resigned from his position as associate editor of The Fugitive and relocated to New York with the conviction that the magazine “set out to introduce a group of new poets and, that done, it has no more to say” (Tate qtd. in Cowan 197). He remained in touch, however, with his fellow Fugitives, particularly Davidson and considered him one of his closest friends. In addition to his continual success as a poet, Tate was a professor, and editor for The Sewanee Review from 1944 to 1946.

Each Fugitive editor would go on to be pioneering figures of Southern Agrarianism, which urged a return to agrarian ways in the age of industrialism. These four men, along with eight other writers who collectively identified themselves as the Twelve Southerners, outlined their philosophies and Agrarianism in 1930 through the essays of I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition.

Walter Clyde Curry

“Will-o’-the Wisp”

Donald Davidson

“Pot Macabre”

“A Dead Romanticist”

“Certain Fallacies in Modern Literature” (Editorial)

William Yandell Elliott

“Epigrams”

“Before Dawn”

James M. Frank

“The Helmeted Minerva”

“Mirrors”

William Frierson

“Reactions on the October Fugitive”

Laura Riding Gottschalk

“Dimensions”

“Initiation”

“Daniel”

Sidney Mttron Hirsch

“Quodlibet”

“To a Dead Lady”

Stanley Johnson

“The Wasted Hour”

“Earth”

Merrill Moore

“Charleston Nights”

“Dawn Honey”

“John’s Threat”

John Crowe Ransom

“Grandgousier”

“First Travels of Max”

“Bell for John Whitesides’ Daughter”

“The Future of Poetry” (Editorial)

Alec Brock Stevenson

“Swamp Moon”

“Complaint of a Melancholy Lover”

Allen Tate

“Nuptials”

“Mary McDonald”

“The Wedding”

“One Escape from the Dilemma” (Editorial)

Robert Penn Warren

“Crusade”

“To a Face in the Crowd”

“Images on the Tomb”

Jesse Ely Wills

“Consider the Heavens”

“The Hills Remember”

Ridley Wills

“Calvary”

“The Experimentor”

Brooker, Peter and Andrew Thacker. “The South and West: Introduction.” The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines: Volume II North America 1894-1960. Eds. Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2012. 501-507. Print.

Cowan, Louise. The Fugitive Group: A Literary History. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP. 1959.

Egerton, John. Speak Now Against the Day : The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South. New York: Knope, 1994. Print.

Fugitives (Group). The Fugitive: A Journal of Poetry. 1922-1925. New York: Johnson Reprint Corp., 1966. Print.

Hoffman, Frederick J., Charles Allen, and Carolyn F. Ulrich. “Modern Poetry and the Little Magazine.” The Little Magazine: A History and a Bibliography. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1946. 109-127. Print.

Kling, Bridget. The Fugitives. Nashville Public Television, 2008. Web.

Kreyling, Michael. “Fugitive Voices: The Reviewer (1921-5); The Lyric (1921-); and The Fugitive (1922-5).” The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines: Volume II North America 1894-1960. Eds. Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2012. 508-522. Print.

McDonald, Gail. “The Fugitives.” In A Companion to Modernist Poetry: Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture. Eds. David E. Chinitz and Gail McDonald. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, 2014. 246-255. Wiley Online Library. Web. 16 Sept. 2015.

“The Fugitive” compiled by Eliana Ferreri (Class of 2016, Davidson College)